On the eve of the Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies’ first year, we take a look back at how faculty and graduate students have been working together through the Simpson Center to develop AIIS graduate studies, along with pathways and support networks for Native students to and at the UW.

On a sunny day in April, Jean Dennison sits tucked away in her office on the fifth floor of the Brutalist labyrinth that is Padelford Hall. She fields a steady stream of calls and meetings as the afternoon light streaks across her impossibly tidy desk. On her computer screen, the text of a Google Doc continuously transforms as though ghosts are pounding away on her keyboard. In fact, the document is being edited remotely by her colleagues, who have been working tirelessly on a major grant proposal that would help fund the University of Washington’s newly created Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies (CAIIS), of which Dennison is a co-director.

“I never used to understand why people couldn’t stay on top of their emails,” Dennison says. “Now I know.”

Associate Professor of American Indian Studies and a citizen of the Osage Nation, Dennison is one of several faculty members, students, staff and community partners that have made the UW a premier site for research, teaching, and service in the field of American Indian and Indigenous Studies (AIIS). AIIS scholars have appointments in many departments across the UW and are particularly well represented in the School of Social Work, Information School, College of Education, and the College of Arts & Sciences, including AIS, Anthropology, Art History, History, English, the Jackson School of International Studies, and others. The UW’s collaborative network around indigeneity so impressed Yale Professor of English Wai Chee Dimock when she came to give the keynote for Earthly Impressions — a two-day symposium on book history and the environmental humanities — that she is featuring its work in her editor’s column for the May issue of PMLA.

Indeed, talk to anyone working in the field and they will tell you that AIIS is having a moment. Dennison and her colleagues identify several factors that have played into the increasing interest in the field locally, nationally, and internationally. Some of the interest, they say, is being driven by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which has mandated that the history of Indian Residential Schools — known in the US as Indian boarding schools — be taught throughout the country. This mandate has not only created a hiring boom of AIIS scholars in Canada, but also in the US, where, just last year, Harvard University hired Professor Phillip Deloria (a citizen of the Dakota Nation and son of the famed Sioux author and activist Vine Deloria, Jr.) as its first-ever tenured professor in the field. “There’s enough of us now to make some noise,” says Associate Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement, Professor of English, and CAIIS co-director Chadwick Allen (Chickasaw ancestry), who will give the first Distinguished Katz Lecture of the 2019–2020 academic year.

Dennison agrees. “We’ve reached a high-water mark of Native faculty at UW,” she says. “And this is what starts to happen when you have enough Native faculty to build excitement.”

While the increased activity and interest around AIIS may be new, the presence of American Indian Studies (AIS) at UW is not. According to the AIS Department website, the development of AIS at UW began in the spring of 1970 following student protests calling for more diversity in UW’s curriculum, faculty, staff and students. An AIS program began in Fall 1970, with faculty involvement from departments that included Anthropology, Art, English, History, Sociology, and Political Science, as well as the Burke Museum. Still, it wasn’t until 2009 when AIS became an academic department. Since then, UW has hired a number of Native and non-Native faculty working in AIIS across a range of disciplines, from medicine, law, and anthropology to information sciences and education.

More recently, the UW has made major investments in institutionalizing American Indian and Indigenous Studies, represented by the vibrant work of colleagues in the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (IWRI) (2007) and the opening of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ — Intellectual House (2015), a longhouse-style facility that gives new visibility to the vitality of Native presence on campus in events like an annual symposium called The Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ: Indigenous Foods and Ecological Knowledge.

As the number of scholars working in the field across the UW has grown, so has the challenge in bringing those scholars together. That’s where the Simpson Center comes in. “Indigenous Studies is inherently collaborative and interdisciplinary, and the Simpson Center is the place for thinking about collaboration at the UW,” says Tony Lucero, Chair of Latin American and Caribbean Studies in the Jackson School of International Studies.

From large-scale collaborations like Creating Survivanceto numerous Society of Scholars projects, AIIS scholars have been producing groundbreaking work through the Simpson Center. In particular, there has been a great deal of activity and excitement around developing and supporting graduate education. Dennison says the Simpson Center has been a crucial “incubator” for many of the graduate studies initiatives that will be housed in CAIIS, from the Summer Institute on Global Indigeneities — now in its third year — to the newly proposed graduate certificate in American Indian and Indigenous Studies.

As American Indian Studies approaches its 50th year at UW and as CAIIS concludes its inaugural year, we decided to take a look back at how faculty and graduate students have been working together to develop AIIS graduate studies and develop pathways and support networks for Native students to and at the UW.

Graduate Certificate in American Indian and Indigenous Studies

Just as the push to create the AIS program in 1970 was driven by Native students, much of the work being done through the Simpson Center is being guided by the needs, interests, and initiative of Native and non-Native graduate students working in the field.

Like so many graduate students who come to the UW to work on American Indian and Indigenous Studies, Laura De Vos (English) found it challenging to cobble together her training in the field, which is — like the Indigenous knowledges from which it emerges — highly interdisciplinary and collaborative. While UW offers an undergraduate degree in American Indian Studies, there’s no graduate program. Instead, graduate students working in a variety of disciplines often find themselves isolated by disciplinary confines, without a cohort or a clear sense of how to find relevant courses across the university. “Many of us don’t know each other because we’re all isolated in our own departments trying to make sense of the field, building our own paths, and cobbling together our training,” De Vos says.

For that reason, De Vos approached Chair and Professor of AIS Chris Teuton (Cherokee Nation) about the possibility of developing a graduate certificate that could not only define a solid path of training, but would also help students build community across disciplines. “I thought it was a great idea,” Teuton says. “And it happened at a perfect time. There’s a lot of graduate coursework across many units being offered right now. The certificate is a way to acknowledge the work that’s being done and shape it in a way that we can help focus and create a training ground that students can matriculate through. It’s also a great way to facilitate a community in which grad students can share and learn from one another.”

Teuton and De Vos have spent the past year working with a core group of faculty and students who have collaborated with stakeholders across campus to draft a graduate certificate proposal that was recently submitted to the Graduate School. The group has also invited administrators of similar programs from the University of Alberta to the University of Minnesota to help think through how to design and administer an effective path of graduate studies in the field.

Beginning next year, the certificate program will offer a course co-taught by Dennison and Associate Professor of Geography Megan Ybarra in Indigenous methodologies, as well as a course taught by Associate Professor of AIS Dian Million (Tanana Athabascan) in Indigenous theories. Students will also create capstone projects that will culminate in public presentations through CAIIS. “One of the things that makes this so compelling is its centering of indigeneity in the right ways,” Dennison says.

Even in its planning stages, De Vos and other grad students say they’re already reaping the benefits of the embryonic certificate. “For me, what’s really made a difference is just being more in touch with faculty and students,” De Vos says. “I’m excited for future students to be introduced to all these different faculty members early on — to work with them, have them on their committees, and have a stronger basis in their training so that they can do work that pushes the envelope.”

Lydia Heberling (Apache and Yaqui ancestry), a doctoral candidate in English, agrees. “It’s awesome to be part of an institution that is actively trying to grow a field in a responsible and relational way,” Heberling says. “The program is really grounded in a commitment to the Coast Salish peoples and it’s also given me the rare opportunity to observe how one develops Indigenous studies programing, which is invaluable as I prepare for the job market.”

Summer Institute on Global Indigeneities

In many ways, the Summer Institute on Global Indigeneities (SIGI) has served as a generative site for much of the rich work being done through and beyond the Simpson Center. Like so many AIIS projects, Lucero says SIGI began as a collective effort with many starting points. “One of the things was all this incredible energy among graduate students and junior faculty,” Lucero says.

Thanks to relationships built while he was a council member of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA), as well as his experience teaching in the Simpson Center co-sponsored Summer Institute in the Arts and Humanities (SIAH), Lucero found models and key collaborators for building a new space of graduate education in AIIS. Since then, SIGI has been held through the Simpson Center in 2016 and 2017, and will be held again this summer, after which it will be housed in CAIIS. For one week, the institute hosts a cohort of twelve graduate students and four faculty members from an international consortium of universities for intensive doctoral training in the field. Says Chadwick Allen, a co-organizer of the summer institute and past president of NAISA, “We wanted a small, intimate group, but we also wanted to balance the ratio so that it wasn’t a single faculty member, but several people coming from different fields, perspectives, and institutions so that we could better articulate a broader sense of the emerging discipline.”

The goal of SIGI is to help doctoral students articulate indigeneity as both an intellectual project and a set of theoretical and political concerns in and beyond the university. The program does this by centering Indigenous ways of knowing and embodied methods for research. Alongside crafting dissertation abstracts and CVs, students are asked to visualize their projects through collages in order to disrupt typical thinking and see their work in new ways. Thanks to University of Utah Professor and SIGI co-facilitator Hokulani Aikau (Kanaka ʻŌiwi Hawaiʻi), each day begins with an Aloha circle, in which students summon their ancestors and set intentions, and ends in a Mahalo circle with expressions of gratitude. “The group mostly consists of Indigenous and self-identified tribal members and students of color for whom that affective work really transforms the experience in extremely meaningful ways,” Lucero says.

For many participants, it’s the day spent in Suquamish with members of the Suquamish Nation that’s most impactful. After sitting in the longhouse with an intergenerational group of elders, adults, and children who share their knowledge, the group heads out onto the water, where they are taught how to canoe. The connection with the Suquamish Nation is part of a larger effort to create strong ties between the UW and tribal communities. This relationship-building has been helped by other Native scholars like Information School Assistant Professor Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Zuni and Tlingit), who has lived at Suquamish since she was a graduate student.

“It was incredibly humbling and impactful to be teachers positioned as learners,” Heberling says of the experience. “The positionality of being on their land and waters, and to derive experience from their modes of knowledge production, acted as a reminder that the knowledge we hold is always contingent on the community with which we work.”

Lucero adds, “it’s a reminder that the work we do is always connected to people and land and we must always be thinking about those relations. Even if those relations are not centered in the students’ projects, those energies guide their approach to their work and how they think about themselves as scholars.”

Though SIGI formally ends with a final symposium where students get ten minutes and two slides to articulate their dissertation projects, the relationships and connections established in SIGI extend well beyond that week. “We all got so close doing that kind of work together,” Heberling says. “We were so sad when everyone had to head back home. But I’ve kept in touch and collaborated with my far-flung colleagues, while here, at UW, we’ve worked hard to keep the momentum going. We wanted that energy all the time.”

For Lucero, it’s the work that comes after SIGI that has, in some ways, been the most exciting. “The way graduate students use SIGI for developing their own ideas has been incredible,” he says. “It catalyzes and energizes new projects.”

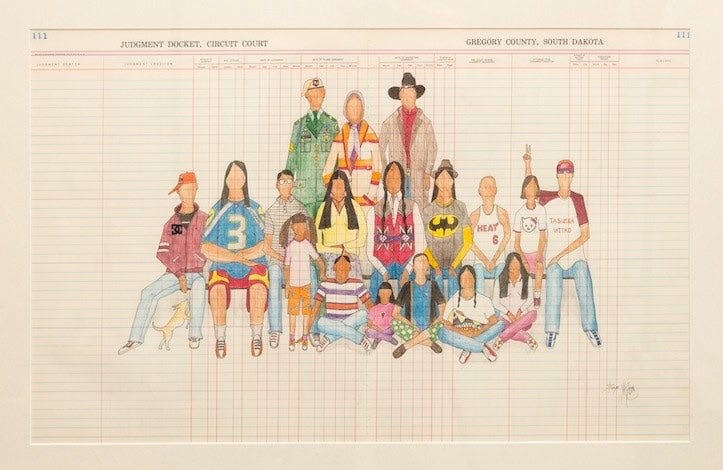

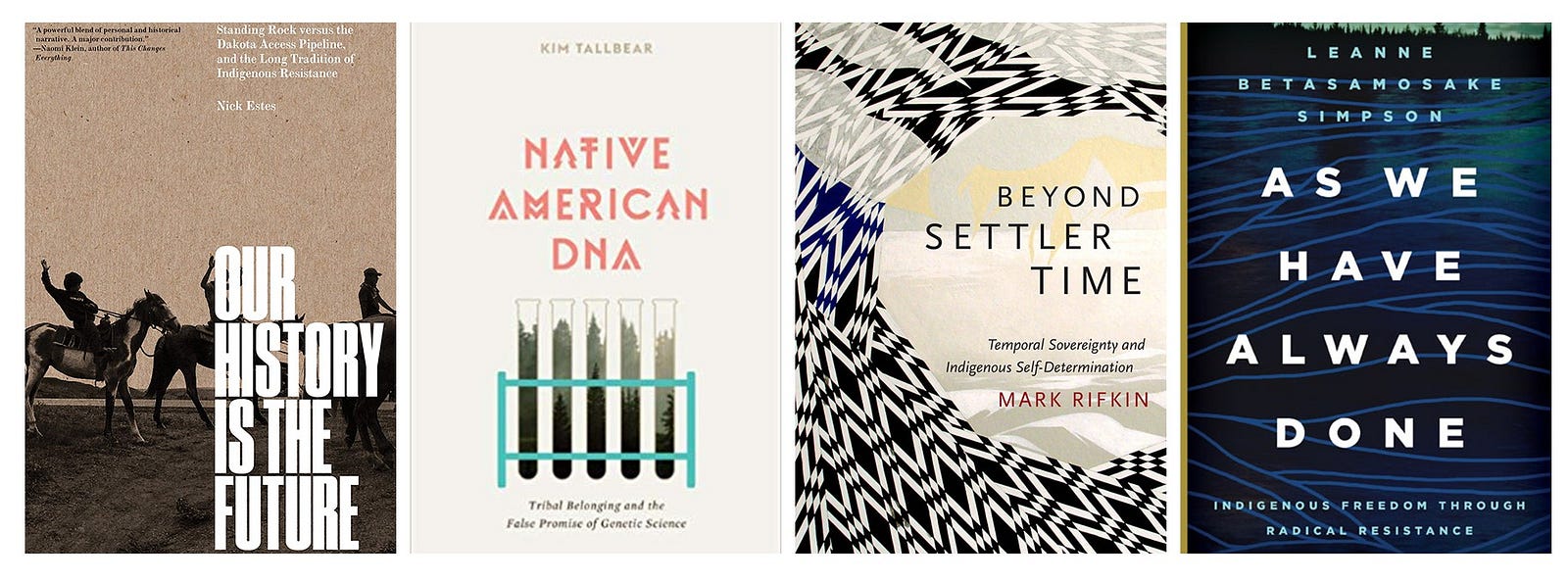

Indigenous Studies Graduate Student Research Cluster

One of those projects has been the Indigenous Studies Graduate Student Research Cluster, which is chaired by Heberling. Throughout the 2018–2019 academic year, students working in AIIS across the university have been meeting monthly to discuss recent scholarship in the field. In almost every instance, the group has had the opportunity to meet with the author of the work they are discussing, from Kim TallBear and Nick Estes to Leanne Simpson and Mark Rifkin. “Experiencing the generosity of these scholars has been huge,” Heberling says. “It really opens the door into the field a bit more and generates even more excitement.”

For members like De Vos, the research cluster has been more than a reading a group. “As grad students, we’re pretty alone, especially in fields like English, where we don’t work in labs. Once we’re in the dissertation stage, we lose the people we might be engaging with and there’s only so many people doing Indigenous studies in our department,” she says. “It’s just really exciting to be with people from all over the university — education, history, all these different backgrounds and training. It’s had a profound effect on my work.”

Beyond acting as a support network for grad students, the research cluster has also played a crucial role in making clear to faculty the need and desire for something like the graduate certificate, which faculty hope will eventually lead to a formal graduate program. Indeed, the motivation and work of graduate students has been a driving factor behind the development of CAIIS. “One of the things that was so interesting in planning CAIIS was that most of the conversations we had with faculty about what resources they wanted wasn’t about research or travel funding, it was about what they needed to better care for their students,” Dennison says.

The success of these efforts can already be seen by Native doctoral students who have gone on to get tenure-track jobs. Dianne Baumann (Blackfeet Nation) will soon join the faculty at the University of Idaho and Patrick Lozar (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes) will join the faculty of the University of Victoria.

Now that the UW can proudly claim to be among a small handful of schools with both a large concentration of Native and Native studies faculty, as well as a burgeoning graduate program, Dennison says the goal of CAIIS will be to create more pathways for Native students to the UW. Adds Dennison, “So much of this work isn’t simply about building an academic community, but a socially supportive community — that’s a big part of what we want CAIIS to do.”

You can learn more about CAIIS and the various AIIS initiatives across campus at the Center’s Meet and Greet from 11 a.m.–2 p.m. on May 31 at the wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ — Intellectual House. Formal remarks from the Provost at noon.